Reframing minimalism: designing an infinite present

What turns minimalist design into good design? Why do some buildings seem old-fashioned and others timeless? How does a minimalist building affect its immediate surroundings? In his essay, futurologist and urban researcher Ludwig Engel answers these questions, at the same time supplying an interesting view on minimalism in architecture and design.

Formative minimalistic architecture

A short while ago, I was standing in Westmount Square in Montreal. This was designed and realised by the icon of architectonic minimalism Mies van der Rohe (“less is more”) between 1964 and 1967 and consists of four structures on a modular grid raised slightly above street level, with a metro station and a small shopping mall underneath. The façades of the four structures – a shoebox with apartments plus a high-rise residential block and two office towers – were all designed on the basis of the same strict grid dimensions as the floor plan: black anodised aluminium frames and dark smoked glass. Apart from the blackness of their dark and extremely elegant appearance, the towers almost seemed to resemble Mies’ famous Lakeshore Drive Apartments in Chicago. Although planning for these began in the late 1940s, it seems to me that the architecture – both here in Montreal and there in Chicago – is incredibly fresh.

Sensational: the icons of minimalist design

Then I was overcome by a sensation that I sometimes experience when I come into contact with icons of minimalist design – be they buildings or everyday objects – or even minimal art. The objects in the vicinity, here predominantly the cars parked in front of and between the buildings on the square, suddenly all seemed so temporal to me. It was as if Mies’ architecture had created a backdrop against which all other designs, having been weighed – and for the most part found wanting – were suddenly relegated to their place in time (80s, 90s, 2000s, etc.). The lack of willingness to compromise, the harshness, clarity and conscious materiality, the absence of transparency regarding the function of the cars that were unlucky enough to be parked in front of these high-rise blocks, of all places, all seemed to duck out of the way, as if wanting to indicate that they knew their place. “We understand: we are too complicated, too ill-considered, too gimmicky, we had our time.” And that time is not now.

Dieter Rams: Principles of good design

It is my theory that this effect cannot simply be addressed by good versus bad design. Instead, it pits timeless, that is to say minimalist design against design that reflects the spirit of its time – which can also be very good design. It is no accident, however, that Dieter Rams, the ultimate godfather of minimalist design, called his ten theses of minimalist design the ten commandments of good design. Just what is it that makes minimalism so different, so appealing? That is what this is about. It is not about the contemporary trends of minimalist consumption patterns and lifestyles that promote a life that can make do with as few things as possible, nor is it about purist interiors and minimalist furnishing concepts, although ultimately, both have something to do with what I am discussing.

Not every future becomes the present

As a futurologist, I am naturally interested in time. Mostly about how people use it to reconcile their experiences and their expectations. The present has a pivotal function here, mediating between the past (= experience) and the future (= expectation). In this tense relationship, people create fragments of what is supposedly to come at any given moment, by promoting some similar possible trends and suppressing others, on the basis of specific experiences. Fragments of what is supposedly to come, because unfortunately, not everything we hope for in the future can come true and not everything that we think should not happen can be prevented. So not every future becomes the present, and we have now built up a substantial pool of past futures – objects, ideas, products and buildings which have been conceived, planned or implemented for futures that have never become reality.

The temporality of eternal waiting

Attached to all these things is a temporality that never allows them to be part of the here and now. These things appear in anticipation of a future that is not to be, eternally waiting for their time that will never come. Remarkably enough, Samuel Beckett’s most famous play “Waiting for Godot”, is about exactly this, making him a minimalist in both a linguistic and dramatic sense. Perhaps it is down to minimalism to hold a mirror up to the past futures?

Potsdamer Platz as a symbol for temporality

Past futures are often best understood in architecture, because the urban context and daily use of a building force it to be honest. The buildings at Potsdamer Platz in Berlin are a good example of how I have to experience the manifestation of temporality in and not just in front of the architecture in my home town, more often than I would like. The Potsdamer Platz was a huge area of wasteland in the heart of the city and was the subject of planning and development by renowned architects from all over the world. The assumption was that Berlin would soon be overrun by people and companies and that the resulting demand for office space at Potsdamer Platz could be met by its new high-rise blocks. It would not take long for the square to become one of the city’s key locations once again, just as it had been before the Second World War. But when, contrary to expectations, neither people nor capital were drawn to Berlin, the square became a dead, non-urban place, visited by indifferent tourists and reluctant Berlin residents.

A city backdrop for products without a future

And even today, after people and capital have finally found their way into the city, the zombie-like existence of the Potsdamer Platz means that it simply has no relevance for the present. At the same time, it will be interesting to see how the Potsdamer Platz will be used in (future) communication. Countless advertisements make use of the sterile skyscraper setting to give a positive slant to their claims of a future-oriented product – whether car, lounge chair, lemon squeezer, or whatever – against the backdrop of a “city of tomorrow”. Mind you, the advertised products are usually extremely old-fashioned and are obviously aimed at a clientèle for whom the city of the future means the city of the past future. The Potsdamer Platz has a temporality that binds it to this past future, making it impossible for it to become the present. It will always remain the backdrop to the city of the future, against which products are advertised that have no future of their own.

Car: temporal. Architecture: timeless.

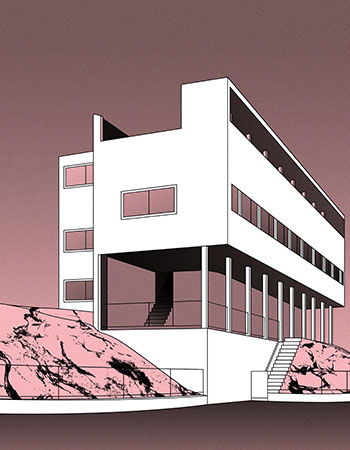

This is not always the case. In 1928, Mercedes promoted its new type 8/38 HP Roadster by photographing it in front of Le Corbusier’s contribution to the Weissenhof Estate. The building had been constructed a year earlier along with a dozen others under the direction of Mies van der Rohe and still looks surprisingly contemporary today. The phenomenon is comparable to the one described above for Westmount Square. If you consider the advertisement from that time, the car you see through today’s eyes looks exactly what it is: a car from 1928. The building in the background, however, looks as if it has just been completed. Actually, Mercedes should not have had to change its advertising motif at all after 1928, merely photograph every new roadster in exactly the same place.

Minimalism is the absolute present

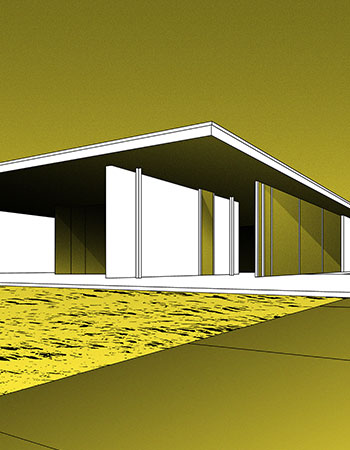

And let me just add my two cents’ worth: minimalism is the absolute present, neither having recourse to nor anticipating any kind of temporality. Minimalist architecture imposes itself on time. Alvaro Siza’s swimming pool in Leça de Palmeira near Porto, Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, Sanaa’s New Museum in New York, the buildings of OFFICE Kersten Geers David van Severen in Belgium or Lacaton & Vassals housing estates in France – they all seem to speak a universal language of timelessness, with their clear geometry, their functional language and their recourse to serial production, repetition, transparency and resolute artificiality. They are like mirrors which, with their Cartesian love of order, give structure to the world around them and reinforce their temporality.

Minimalist architecture is a high-quality stage

The architectures mentioned change the observer’s perception of space. The surroundings gain a speculative temporality. The object itself seems timeless, the temporality of the surroundings is highlighted. The temporality of the other designed objects in the vicinity emerges. And isn’t it even the case that a well-composed object – whatever era or taste it represents – reveals its quality in minimalist environment? Minimalism in architecture is like a stage of such high quality that it quickly becomes apparent which actors have overstretched themselves and which have the quality to fill it with their performance.

Reducing visibility opens up new possibilities

Minimalism is not elitist, it uncovers what is already there. Minimalism ensures transparency, both for the way the object functions and for the motivation behind its production. While Robert Smithson was pouring earth between mirrors at his Non-Sites and Dan Flavin with fluorescent tubes and Donald Judd with aluminium frames were making the contextuality of an installation part of the installation itself, the observer experience was being transformed from aesthetic engagement in the visual-spatial frame set by the artwork to an event outside the artwork. Today, as an ephemeral, invisible and digital layer changes our perception of the present, the further reduction of visibility opens up the possibilities and freedoms of contextual interpretability. A sentence is not usually the answer, just the tip of the iceberg, but a skilfully positioned sentence can have a far greater effect on the listener than an elaborately formulated argument.

A minimalist object has an effect on its surroundings

This also describes the strength of minimalist design. It enhances the perceptive ability of the observer. The more inventive and imaginative a person is, the more knowledge and intuition they possess, the greater the effect a design has on them that does not formulate its design aspirations, but merely outlines them. And one more thing: it is not only observers and users who can see more, the sharper their eyes and mind are, the environment itself is also sharply defined by the contrast to the minimalistically designed object.

About the author

Ludwig Engel studied economics, cultural history and the science of communication in Berlin, Shanghai and Frankfurt/Oder and is kept busy by teaching assignments, exhibitions, publications and consultancy projects that focus on urban utopias, long-term strategic planning and digital age issues. He was part of the “Society and Technology Research Group” at Daimler AG, is a founder member of the “Interdisciplinary Forum on Neuro-Urbanism” and is co-editor of “Speculations. Transformations. Thoughts on the Future of Germany’s Cities and Regions”, as well as other anthologies on subjects such as the city of the future, artificial intelligence and social transformation.